The life science industry faces a critical inflection point. Women represent half the global population and make 80% of healthcare decisions, yet systemic gender bias in clinical research, data collection, and product development has created a healthcare ecosystem that fails women at unprecedented levels. This is not merely an equity issue but a significant business opportunity that pharmaceutical, biotechnology, and medical device companies can no longer afford to ignore. Closing the women's health gap could generate $1 trillion in annual global GDP by 2040, with a $3 return on every $1 invested.[1][2][3][4][5]

Understanding the women's health gap

The McKinsey Health Institute, in collaboration with the World Economic Forum, defines the women's health gap as the difference in the amount of time women spend in poor health compared to men, measured using global health data across diseases, demographics, and income levels. The study defines this gap as the inequality in healthy life expectancy, specifically, that women spend 25% more of their lives in poor health than men, even though they live longer overall. This gap reflects systemic barriers in diagnosis, research, care delivery, treatment access, and health financing that disproportionately disadvantage women.[4][1]

Women spend 25% more of their lives in poor health than men.

McKinsey quantifies the gap using data from the University of Washington's Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) Global Burden of Disease (GBD) dataset. The measure used is disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), a combined metric of years of life lost due to premature mortality and years lived with disability due to disease or poor health. Based on these measures, the study found that the global women's health gap equals 75 million DALYs lost each year, meaning 75 million years of life are lost annually to illness or early death that could be avoided if women's health outcomes matched men's. Closing this gap would be equivalent to giving every woman seven additional healthy days per year, resulting in $1 trillion in annual global GDP gains by 2040. More than half of the women's health gap occurs during women's working years (ages 20 to 60), meaning that much of the economic loss is due to reduced productivity and preventable illness in the labor force.[1][4]

The McKinsey study modeled 64 disease categories accounting for 86% of the global burden of disease in women and quantified both the health and economic outcomes of closing that gap. It also examined nine high-impact conditions (ischemic heart disease, breast cancer, cervical cancer, maternal hypertensive disorder, postpartum hemorrhage, menopause, premenstrual syndrome, migraine, and endometriosis) which together account for one-third of the total gap and represent a $400 billion opportunity in global GDP by 2040 if addressed.[4][1]

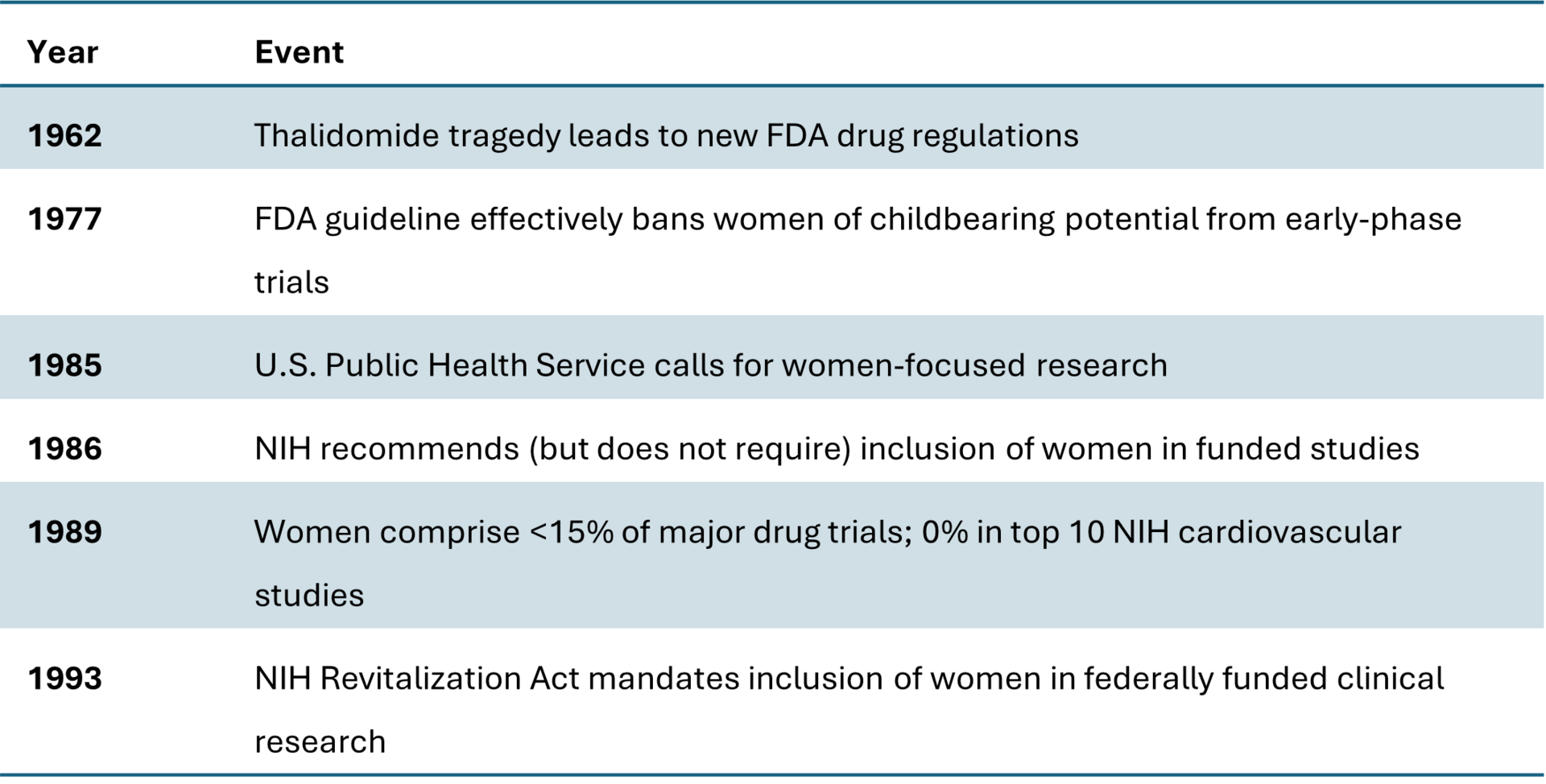

Historical context: The exclusion of women from clinical research before 1993

Before 1993, clinical research in the United States was deeply biased toward male participation, with policies and practices that systematically excluded women, especially women of childbearing age, from most drug and device trials. The numbers and historical records show how pervasive and consequential this exclusion was.

In 1977, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued guidelines recommending that "women of childbearing potential" be excluded from Phase I and early Phase II clinical trials until reproductive toxicity studies were completed and drug safety could be established. Although the policy was framed as protecting potential pregnancies, it resulted in the effective exclusion of all premenopausal women from early-stage research. This guideline remained active for 16 years and fundamentally shaped the gender imbalance in biomedical research that persisted into the 1990s.[6]

During that time, most clinical trials were conducted exclusively on men, leading to a data foundation that defined the "average patient" as male. A 1990 GAO report confirmed that bias was pervasive at the NIH, noting widespread noncompliance with inclusion guidance issued in the 1980s and a complete lack of sex-specific data analysis. By 1989, women accounted for fewer than 15% of participants in major drug trials, and none of the NIH's top 10 cardiovascular studies included women at all. Large landmark trials, such as those on low-dose aspirin for heart attack prevention, included only male subjects, leading to clinical recommendations that did not hold true for women and contributed to misdiagnosis and under-treatment of female heart disease patients for decades.[6]

Amid growing criticism, the NIH began to issue "encouragement" for inclusion of women in 1986 but did not enforce compliance. By the end of the decade, only a small fraction of federally funded trials included women, and sex-based data were seldom reported. Women's health advocates and AIDS activists pressured federal agencies to reverse exclusionary practices, emphasizing the ethical and scientific costs of excluding women from drug research.

The culmination came with the NIH Revitalization Act of 1993, which legally mandated inclusion of women and minorities in NIH-funded clinical trials. The Act required that women and minorities must be included in Phase III clinical research unless scientifically justified otherwise, that study designs must allow for analysis of whether variables affect women differently, and that cost could no longer be cited as a reason for excluding women. The law formally reversed the 1977 FDA guideline, marking the first time that inclusion was a legal requirement and setting the foundation for modern sex and gender-based research standards.[6]

Timeline of key events in women's clinical research

The decades-long exclusion of women created a structural data void that underpins many of the safety disparities observed today, such as higher adverse drug reaction rates and inadequate dosing accuracy for women. The modern policy fixes of the 1990s were thus a corrective response to more than half a century of gender bias in biomedical evidence.

The scope of bias in life sciences research

Gender bias in clinical research manifests at every stage of drug and device development, creating compounding effects throughout the healthcare ecosystem. Women were effectively barred from early-phase clinical trials until 1993, when Congress codified new NIH inclusion policies. Yet three decades later, the underrepresentation persists with troubling consistency.[6]

Women account for only 22% of Phase I clinical trial participants, and just 29 to 34% of participants in industry-sponsored early-phase trials. Even in therapeutic areas where women constitute the majority of patients, their representation in trials remains disproportionately low. Women make up 60% of psychiatric disorder patients but only 42% of trial participants, 51% of cancer patients but only 41% of trial participants, and 49% of cardiovascular disease patients but only 41.9% of trial participants. This disparity is even more pronounced in conditions like heart disease, where research historically focused on men despite women experiencing higher morbidity and mortality.[7][8][9][10][11]

The consequences extend beyond enrollment numbers. Women-specific conditions receive shockingly inadequate research funding. Premenstrual syndrome, menopause, maternal hemorrhage, maternal hypertensive disorders, cervical cancer, and endometriosis collectively account for 14% of the total women's health gap but received less than 1% of cumulative research funding allocated to conditions driving the health gap between 2019 and 2023. Female-only conditions represent just 4% of pharmaceutical pipelines, and only 10.8% of NIH funding is allocated to women's research.[12][1][6]

The impacts: The data imbalance creates tangible risks

The exclusion of women from clinical research has created a dangerous information vacuum with real-world consequences. Women experience adverse drug reactions at 1.5 to 1.7 times the rate of men across all drug classes. Between 1997 and 2000, eight of ten drugs withdrawn from the U.S. market posed greater health risks to women than men. Over four decades, 30% of drug recalls were tied to women-related safety issues.[13][14][15][12]

The biological basis for these disparities is increasingly clear. Women administered standard drug doses experience higher blood concentrations and longer elimination times than men for most FDA-approved drugs. Among 86 drugs evaluated, 76 demonstrated higher pharmacokinetic values in women, and sex-biased pharmacokinetics predicted the direction of sex-biased adverse drug reactions in 88% of cases. This pattern suggests that women are routinely overmedicated, a problem that becomes even more critical given that women use more medications per year than men (5.0 versus 3.7) and are more likely to engage in polypharmacy.[16]

The data gaps extend to medical devices. Female-specific device recalls have been tied to inadequate premarket testing and insufficient adverse event reporting. One transcervical contraceptive device remained on the market for 16 years despite 32,000 complaints to the manufacturer that were never reported to the FDA as adverse events, ultimately resulting in a $1.6 billion settlement.[17]

The downstream cascade through the healthcare ecosystem

Gender bias in life sciences research creates ripple effects throughout the entire healthcare delivery system, affecting preventive care, insurance coverage, reimbursement structures, and ultimately driving inefficiencies that impact pharmaceutical and biotech companies' long-term market potential.

The insurance industry perpetuates and amplifies these biases. Before the Affordable Care Act, gender rating practices charged women approximately $1 billion more annually than men for health coverage. Even today, working women in the United States spend 18% more on out-of-pocket healthcare costs than men, translating to $15 billion annually in additional expenses, even when excluding pregnancy-related services. This gender-based financial burden compounds the well-documented gender wage gap, forcing women into difficult choices between necessary care and affordability.[18][19][20][21]

Reimbursement structures reflect and reinforce gender disparities. Analysis of 55 gender-specific surgical procedures reveals that 75% had lower relative value units for procedures on female patients in 2023, with male procedures reimbursed 30% higher on average. For facility reimbursement, 64% were higher for procedures on male patients, correlating to an average of $75.73 more for male procedures. These disparities have shown minimal improvement over three decades.[22][23]

The impact on preventive health creates a self-perpetuating cycle. Women face coverage exclusions for services they are likely to need, leaving them vulnerable to higher costs and denied claims. Insurance plans often exclude maintenance therapy for chronic conditions disproportionately prevalent in women, effectively denying coverage for preexisting conditions through different means. This discourages women from seeking preventive care, leading to later-stage diagnoses, more expensive treatments, and worse outcomes.[24]

These systemic biases ultimately constrain market potential for pharmaceutical and biotech companies. When women face financial barriers to care, diagnostic delays, and insurance coverage gaps, they are less likely to access treatments, remain on therapy, or achieve optimal health outcomes. Pay-for-performance reimbursement standards increasingly evaluate hospitals and physicians based on quality measurements, and gender disparities in healthcare negatively impact these reimbursements. When healthcare providers fail to diagnose and treat conditions like heart attacks in women, they lose reimbursement money under the Affordable Care Act.[25]

The compelling business case for pharma and biotech

Despite these challenges, the women's health market represents one of the most significant growth opportunities in the life sciences sector. The global women's health therapeutics market reached $46.69 billion in 2025 and is forecast to grow to $66.62 billion by 2034. Women's health venture capital investment reached an all-time high of $2.6 billion in 2024, up from $1.7 billion in 2023, with biopharma investments accounting for 34% of the total.[26][27][28]

The economic rationale extends far beyond market size projections. Most pharmaceutical companies derive more than 60% of their revenue from therapies for diseases that uniquely, differently, or disproportionately affect women, including autoimmune diseases, mental health disorders, osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, and certain cancers. More than 55% of assets in Phase II and III clinical trials target conditions that disproportionately or more intensely affect women.[28][12]

Investing in gender-equitable research delivers measurable returns. McKinsey analysis indicates that investing in women's health improvements yields a return on investment of approximately $3 for every $1 invested globally, with higher-income settings seeing returns around $3.50 per dollar. Investing $350 million in research focused on women's health could yield $14 billion in economic returns. Doubling investment in coronary artery disease research for women alone could save nearly $2 billion in healthcare costs.[2][4]

The market opportunity extends across the lifecycle and therapeutic spectrum. The potential market for addressing menopause-related symptoms could increase eightfold to more than $40 billion. Conditions like endometriosis, polycystic ovarian syndrome, postpartum depression, and premenstrual dysphoric disorder represent substantial unmet needs where innovation is accelerating. Digital health, AI-powered diagnostics, hormone-aware drug delivery systems, and personalized medicine platforms incorporating genetic profiles are opening new commercial opportunities.[5][29][30][31][32]

Medical device companies face similar opportunities. The number of medical devices approved for women's health indications is growing, spanning female cancers, urinary incontinence, pelvic floor disorders, female infertility, pregnancy-related complications, and postpartum hemorrhage. Successful innovations like the JADA system for treating postpartum hemorrhage demonstrated 40% sales growth in 2024 and expanded to new geographies.[33]

Strategic imperatives for life science leaders

Life science executives who recognize women's health as a strategic priority rather than a niche market position their organizations for sustained competitive advantage. Several concrete actions can accelerate progress and capture value.

First, companies must commit to inclusive clinical trial design from the earliest phases of development. This includes ensuring adequate representation of women in Phase I trials, analyzing and reporting sex-disaggregated data for all studies, and studying sex differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. The FDA has strengthened guidance on evaluating sex differences in clinical investigations, creating regulatory incentives for this approach.[34][35]

Second, pharmaceutical and biotech companies should reassess their research and development priorities to align investment with disease burden rather than historical funding patterns. Women-specific conditions that constitute 14% of the women's health gap receive less than 1% of research funding, while conditions representing 2% of the burden receive more than six times the investment. Closing these gaps represents white space for innovation and commercial opportunity.[1]

Third, medical device companies must strengthen premarket testing protocols to ensure products are evaluated in representative populations. The history of device recalls disproportionately affecting women underscores the business risk of inadequate gender-inclusive testing.[36]

Fourth, companies should recognize that many blockbuster therapeutic areas inherently involve women's health. Cardiovascular disease, autoimmune disorders, neurodegenerative conditions, and psychiatric illnesses all affect women differently or disproportionately. Integrating gender-specific insights into product development, clinical decision support, and commercialization strategies for these established markets can differentiate offerings and improve outcomes.[30][12]

Fifth, organizations should leverage artificial intelligence and real-world data to address historical data gaps. AI holds tremendous potential for women's health applications, but only if datasets include diverse, representative populations and algorithms are audited for bias. Companies that proactively address bias in AI-driven drug discovery, clinical trial simulation, and diagnostics will avoid reproducing systemic inequities in next-generation technologies.[37][38]

Finally, life science companies should align their commercial strategies with the evolving payer landscape. As value-based care models proliferate and payers face pressure to address gender health disparities, products supported by gender-equitable evidence and demonstrated outcomes in diverse populations will be better positioned for coverage and reimbursement.[24][25]

Turning equity into innovation and growth

The business case for addressing gender bias in the life sciences is unequivocal. The data imbalances created by decades of excluding women from research have generated substantial safety risks, constrained market opportunities, and contributed to inefficiencies throughout the healthcare ecosystem. These inefficiencies ultimately limit the commercial potential for pharmaceutical, biotechnology, and medical device companies.

Conversely, companies that invest in gender-equitable research, inclusive clinical trials, and products designed for the realities of female biology position themselves to capture a $1 trillion annual market opportunity while delivering improved health outcomes, reducing safety risks, and creating positive spillover effects across families and communities.[2][4][1]

The momentum is building. Venture capital flowing into women's health reached record levels in 2024. Major pharmaceutical companies are beginning to recognize that women's health already represents the majority of their revenue base. Government agencies, from ARPA-H's Sprint for Women's Health to NIH's strategic plan, are directing resources toward closing the gap.[27][39][40][12][28]

For life science leaders, the strategic question is not whether to invest in women's health but how quickly to scale these investments relative to competitors. Companies that move decisively will not only fulfill an ethical imperative but will also unlock substantial commercial returns, strengthen their market position, and contribute to building a more equitable and efficient healthcare system.

The data is clear, the market opportunity is substantial, and the time to act is now.

References

McKinsey Health Institute. "Blueprint to Close the Women's Health Gap: How to Improve Lives and Economies for All." McKinsey & Company, 2025, www.mckinsey.com/mhi/our-insights/blueprint-to-close-the-womens-health-gap-how-to-improve-lives-and-economies-for-all.

Sinha, Sylvana Q. "Women's Health: A Trillion-Dollar Investment Frontier." Forbes, 16 Feb. 2025, www.forbes.com/sites/sylvanaqsinha/2025/02/16/womens-health-a-trillion-dollar-investment-frontier/.

FTI Consulting. "Women's Health: Unlocking Immense ROI for the Predominant Healthcare Decision-Maker." FTI Consulting, 4 Aug. 2025, www.fticonsulting.com/insights/articles/womens-health-unlocking-roi-healthcare-decision-maker.

McKinsey Health Institute. "Closing the Women's Health Gap: A $1 Trillion Dollar Opportunity to Improve Lives and Economies." McKinsey & Company, 16 Jan. 2024, www.mckinsey.com/mhi/our-insights/closing-the-womens-health-gap-a-1-trillion-dollar-opportunity-to-improve-lives-and-economies.

World Economic Forum. "Why Women's Health Is a $1 Trillion Opportunity to Seize." World Economic Forum, 2 June 2025, www.weforum.org/stories/2025/05/women-s-health-trillion-dollar-opportunity-investment/.

Perelel Health. "16 Alarming Facts About the Women's Health Research Gap." Perelel, 9 Jan. 2025, perelelhealth.com/blogs/news/womens-health-research-gap.

Labiotech. "Women in Clinical Trials: Why Are They Still Underrepresented?" Labiotech, 10 Mar. 2025, www.labiotech.eu/in-depth/women-clinical-trial/.

World Economic Forum. "There's a Women's Health Gap. Here's How to Close It." World Economic Forum, 2 June 2025, www.weforum.org/stories/2025/01/theres-a-womens-health-gap-heres-how-to-close-it/.

Harvard Medical School. "More Data Needed." Harvard Medicine News, 11 Dec. 2024, hms.harvard.edu/news/more-data-needed.

Clinical Trials Arena. "Underrepresentation of Women in Early-Stage Clinical Trials." Clinical Trials Arena, 16 Oct. 2022, www.clinicaltrialsarena.com/features/underrepresentation-women-early-stage-clinical-trials/.

Holdcroft, Anita. "Gender Bias in Research: How Does It Affect Evidence Based Medicine?" Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, vol. 100, no. 1, 2007, pp. 2-3, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1761670/.

McKinsey & Company. "How Biopharma Can Close the Gap in Women's Health." McKinsey & Company, 21 Jan. 2025, www.mckinsey.com/industries/life-sciences/our-insights/closing-the-womens-health-gap-biopharmas-untapped-opportunity.

Applied Clinical Trials. "Gender Bias in the Clinical Evaluation of Drugs." Applied Clinical Trials Online, 15 Dec. 2020, www.appliedclinicaltrialsonline.com/view/gender-bias-in-the-clinical-evaluation-of-drugs.

Rademaker, Marius. "Do Women Have More Adverse Drug Reactions?" American Journal of Clinical Dermatology, vol. 2, no. 6, 2001, pp. 349-51, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11770389/.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. "Food and Drug Administration: Beyond the 2001 Government Accountability Office Report." Contemporary Clinical Trials, vol. 97, 2020, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33635140/.

Zucker, Irving, and Brian J. Prendergast. "Sex Differences in Pharmacokinetics Predict Adverse Drug Reactions in Women." Biology of Sex Differences, vol. 11, 2020, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7275616/.

Chen, Aimee M., and Lisa M. Haddad. "Is the FDA Failing Women?" AMA Journal of Ethics, vol. 23, no. 9, 2021, pp. E741-746, journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/fda-failing-women/2021-09.

Deloitte. "Closing the Cost Gap: Strategies to Advance Women's Health Equity." Deloitte US, 26 Feb. 2025, www.deloitte.com/us/en/Industries/life-sciences-health-care/articles/womens-health-equity-disparities.html.

World Economic Forum. "US Women Are Paying More for Healthcare Than Men Every Year." World Economic Forum, 2 June 2025, www.weforum.org/stories/2023/10/healthcare-equality-united-states-gender-gap/.

Families USA. "The High Cost of Gender Rating." Families USA, 15 Mar. 2020, www.familiesusa.org/resources/the-high-cost-of-gender-rating/.

National Women's Law Center. "Turning to Fairness: Insurance Discrimination Against Women Today and the Affordable Care Act." NWLC, 12 Sept. 2022, nwlc.org/resource/turning-to-fairness-insurance-discrimination-against-women-today-and-the-affordable-care-act/.

Anderson, Cristina L., et al. "Reimbursement of Surgical Care on Male Versus Female Anatomies." Journal of Women's Health, vol. 34, no. 5, 2025, pp. 613-618, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39978776/.

Houman, Jamin V., et al. "Price and Prejudice: Reimbursement of Surgical Care on Male Versus Female Anatomies." Journal of Women's Health, vol. 34, no. 2, 2025, pp. 192-198, www.liebertpub.com/doi/abs/10.1089/jwh.2024.0984.

Sobel, Laurie, et al. "Women's Health Coverage Since the ACA: Improvements for Most, Insurer Exclusions Remain." Commonwealth Fund, 1 Aug. 2016, www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2016/aug/womens-health-coverage-aca-improvements-most-insurer-exclusions.

Hoffman, Michelle R. "How Gender Disparities in Healthcare Hurt Hospitals' Pay for Performance." Washington University Law Review, vol. 95, no. 4, 2017, pp. 1029-1056, journals.library.wustl.edu/lawreview/article/id/6246/.

Precedence Research. "Women's Health Therapeutics Market Size and Forecast 2025 to 2034." Precedence Research, 12 June 2025, www.precedenceresearch.com/womens-health-therapeutics-market.

Silicon Valley Bank. "Innovation in Women's Health 2025." SVB, 31 Dec. 2024, www.svb.com/trends-insights/reports/womens-health-report/.

BiopharmaDive. "Women's Health Faces Growing Headwinds, Despite Jump in Venture Funding." BiopharmaDive, 12 May 2025, www.biopharmadive.com/news/womens-health-venture-funding-increase-headwinds-barriers/747969/.

NFX. "Women's Health 2.0: Beyond Fertility." NFX, 13 Aug. 2025, www.nfx.com/post/womens-health.

MassBio. "Women's Health: Innovations and Therapeutics." MassBio, 3 Sept. 2025, www.massbio.org/news/recent-news/womens-health-innovations-and-therapeutics/.

Boston Consulting Group. "Improving Women's Health Is a $100B Plus Opportunity." BCG, 22 June 2025, www.bcg.com/publications/2025/improving-womens-health-opportunity.

Premier Research. "Shifting Priorities in Women's Health: 6 Trends to Watch in Clinical Research." Premier Research, 16 June 2025, premier-research.com/perspectives/shifting-priorities-in-womens-health-6-trends-to-watch-in-clinical-research/.

Medical Device Network. "Women's Health: Breakthrough Medtech Devices and Investment." Medical Device Network, 21 Oct. 2025, www.medicaldevice-network.com/analyst-comment/womens-health-medtech-investment-momentum/.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. "Evaluation of Sex Differences in Clinical Investigations." FDA, 1 Apr. 2025, www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/evaluation-sex-differences-clinical-investigations.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. "Study of Sex Differences in the Clinical Evaluation of Medical Products." FDA, 24 July 2025, www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/study-sex-differences-clinical-evaluation-medical-products.

Whitcomb, Brandon W., et al. "Overview of High-Risk Medical Device Recalls in Obstetrics and Gynecology from 2010 to 2016." American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, vol. 217, no. 6, 2017, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0002937817304593.

Drug Target Review. "Making Sense of AI: Bias, Trust and Transparency in Pharma R&D." Drug Target Review, 10 Sept. 2025, www.drugtargetreview.com/article/183358/making-sense-of-ai-bias-trust-and-transparency-in-pharma-rd/.

Landi, Isabella, et al. "Exploring Bias Risks in Artificial Intelligence and Targeted Medicines Manufacturing." Digital Health, vol. 10, 2024, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11483979/.

ARPA-H. "Sprint for Women's Health." Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health, 31 Oct. 2024, arpa-h.gov/explore-funding/initiatives-and-sprints/sprint-for-womens-health.

National Institutes of Health Office of Research on Women's Health. "NIH-Wide Strategic Plan for Research on the Health of Women." NIH ORWH, 14 May 2024, orwh.od.nih.gov/about/strategic-plan.