History offers a map for navigating today's AI expectations

In June 2000, President Bill Clinton stood in the East Room of the White House and declared that the Human Genome Project would "revolutionize the diagnosis, prevention and treatment of most, if not all, human diseases." Francis Collins, then director of the National Human Genome Research Institute, predicted that by 2010, genetic tests for common diseases would be widely available, soon followed by personalized preventive therapies tailored to each individual.[1][2]

A decade later, the headlines told a more sober story. The New York Times reported that the genetic map had yielded "few new cures," while Scientific American described the genomic revolution as "postponed." After $2.7 billion and years of work, many observers questioned whether the Human Genome Project had been overhyped.[3][4][5]

The public conversation and excitement around artificial intelligence today bears similarities to public discourse and expectations around the Human Genome Project. Are there echoes in how both technologies have been hyped, adopted and perceived? Can the lessons learned from the Human Genome Project experience help us ground our expectations of AI more realistically?[6]

Let us look at the Human Genome Project as a reference point. By examining where early expectations for genomics proved accurate, where they did not and how perceptions evolved over 25 years, we can draw practical lessons that may help life science leaders navigate AI adoption with more discipline, less volatility and better-aligned expectations.[7][8]

Where we are now with AI

The data from 2025 paints a sobering picture. McKinsey's latest global survey reveals that while nearly 80% of businesses report using generative AI, an equal proportion cite "no significant impact on the bottom line." More dramatically, MIT's NANDA initiative found that approximately 95% of enterprise generative AI pilot programs are failing to achieve rapid revenue acceleration, delivering little to no measurable impact on profit and loss statements.[9][10]

Gartner's 2025 Hype Cycle for Artificial Intelligence confirms what many life sciences leaders are experiencing firsthand: generative AI has entered the "Trough of Disillusionment." This is the phase where inflated expectations meet implementation realities, where pilot programs stall and where the gap between promise and performance becomes painfully apparent.[11][12]

In the life sciences sector specifically, AI adoption remains uneven. Pharmaceutical and biotech companies are using AI most actively in drug discovery, trial operations and commercial analytics, yet many initiatives are still confined to pilots or isolated use cases rather than scaled, production-grade deployments. When IQVIA surveyed the sector in July 2025, 81% of respondents identified achieving analytic accuracy and operational efficiency as their top barrier to broader AI adoption.[13][14][15]

The challenges extend beyond technology. At the ACDM AI/ML Conference in Frankfurt in mid-2025, industry leaders acknowledged that the biggest adoption barrier is not AI capability itself but organizational readiness. Change management difficulties, workforce resistance rooted in job security fears and the struggle to integrate AI into existing workflows emerged as the primary impediments.[16]

We are in a phase of understanding the span and breadth of AI's capabilities and applications, all while concurrently advancing the technology at a rapid pace. The excitement of ChatGPT's breakthrough in late 2022 and the explosive growth through 2023-2024 represented a peak of expectations that is now giving way to the harder work of practical implementation.[17][18][19]

Understanding the Gartner Hype Cycle

To understand where AI sits today and where it might be headed, it is helpful to briefly revisit the Gartner Hype Cycle, a framework widely used in consulting to track how expectations evolve around emerging technologies.

The Hype Cycle does not track sales volume or actual usage. Instead, it maps the evolution of expectations and sentiment. It consists of five distinct phases:

Innovation Trigger. A technological breakthrough generates initial publicity and interest. Early proof-of-concept stories proliferate, but usable products often do not yet exist.

Peak of Inflated Expectations. Early publicity produces success stories, often accompanied by numerous failures. Some companies take action, but many do not. Media coverage intensifies, and expectations reach unrealistic levels.

Trough of Disillusionment. Interest wanes as implementations fail to deliver on inflated promises. Providers consolidate, fail or pivot. Investment continues only if surviving providers improve their offerings to satisfy early adopters.

Slope of Enlightenment. More concrete instances of how the technology benefits organizations crystallize and become more widely understood. Second and third-generation products emerge. More enterprises fund pilots, though conservative companies remain cautious.

Plateau of Productivity. Mainstream adoption accelerates. Criteria for assessing provider viability are clearly defined. The technology's broad market applicability and relevance are paying off.

According to Gartner's 2025 analysis, no AI technologies have yet reached the plateau. AI agents, AI-ready data, responsible AI and AI engineering cluster at or near the Peak of Inflated Expectations. Foundation models, synthetic data, edge AI and generative AI itself have descended into the Trough of Disillusionment. More mature capabilities like model distillation and knowledge graphs are climbing the Slope of Enlightenment, while quantum AI and artificial general intelligence remain at the Innovation Trigger stage.[20][11]

For life sciences leaders, this positioning signals that expectations are in the process of being reset, and that the most visible technologies are precisely those facing the steepest adjustment.

The S-Curve: Actual adoption behind the hype

While the Hype Cycle tracks expectations, a different model can help explain actual adoption: the S-Curve, or Diffusion of Innovations, developed by sociologist Everett Rogers.

The S-Curve segments adopters into five categories based on when they embrace new technology:

Innovators (2.5% of the market) are risk-takers willing to try unproven solutions. They have the financial resources to absorb failures and the technical sophistication to work with immature products.

Early Adopters (13.5%) are visionaries who can see strategic opportunities and are comfortable with calculated risks. They adopt technologies before proven business cases exist but expect to gain competitive advantage from being early.

Early Majority (34%) are pragmatists who wait for proof points before committing. They need references, case studies and evidence that implementations deliver tangible value. They represent the beginning of mainstream adoption.

Late Majority (34%) are conservatives who adopt only when technology becomes standard practice. They are skeptical of change and adopt primarily to avoid falling behind competitors or to meet industry requirements.

Laggards (16%) resist change and adopt only when they have no alternative.

Between Early Adopters and the Early Majority lies a critical gap often called "the chasm." Many promising technologies fail to cross this chasm because the pragmatic majority demands different value propositions, risk profiles and implementation support than visionary early adopters.

Putting the Hype Cycle and the S-Curve side by side reveals an important pattern. When a technology sits at the Peak of Inflated Expectations, adoption is still typically concentrated among innovators and early adopters. The Trough of Disillusionment often coincides with the difficult transition from early adopters to the early majority, when requirements around reliability, integration and change management become much more demanding.

AI in life sciences today appears to be somewhere in this transition. Adoption is broader than early pilots in a few innovation teams, yet many organizations are still struggling to convert promising experiments into stable, scaled capabilities.[15][21]

The Human Genome Project: A paradigm-shifting parallel

The Human Genome Project shares a fundamental characteristic with artificial intelligence in life sciences: both represent major paradigm-shifting advancements anticipated to have transformative impact on the industry.[22][23][7]

The promise (1990-2000)

When the Human Genome Project officially launched in 1990 with a projected cost of $3 billion over 15 years, it faced significant skepticism. A letter-writing campaign led by Professor Martin Rechsteiner of the University of Utah involved 55 scientists from 33 institutions who argued against federal funding.[24]

Critics claimed the project was too expensive, that it would be merely a "repetitive technical exercise" yielding "no interesting biological information" and that resources would be better spent on smaller investigator-initiated projects targeting "medically important loci" rather than sequencing the entire genome. Professor John Hildebrand of the University of Arizona wrote that "our society cannot afford that kind of price tag on such an ill-considered initiative."[24]

Despite this opposition, Congress proved more supportive than many biologists. Legislators understood the appeal of international competitiveness, potential industrial spin-offs, economic benefits and more effective approaches to disease. A 1988 National Academy of Sciences committee report endorsed the project, and the tide of opinion turned.[7]

Proponents made sweeping promises. James Watson, a Nobel laureate who headed the National Center for Human Genome Research, declared in 1990 that "it's essentially immoral not to get it done as fast as possible." Scientists described the HGP as "the single most important project in biology and the biomedical sciences, one that will permanently change biology and medicine."[25][22][7]

The project achieved a major milestone ahead of schedule. On June 26, 2000, at a White House ceremony attended by politicians, ambassadors, scientists, executives and journalists, the International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium announced completion of a working draft of the human genome. President Clinton's proclamation that this would "revolutionize" diagnosis, prevention and treatment of diseases echoed around the world.[26][1]

In 1999, Francis Collins had painted a concrete vision: genetic tests indicating risk for heart disease, cancer and other common conditions would be available by 2010, followed by preventive therapies tailored to individuals. Public expectations ran high. Surveys from the era show that many people expected substantial medical breakthroughs within five to ten years.[2][27][6]

The trough (2003-2013)

The Human Genome Project published its "complete" sequence in April 2003, more than two years ahead of schedule and under budget. In reality, they had mapped approximately 92% of the genome; the remaining 8% would take nearly 20 more years to sequence.[28][29][30]

The next decade, however, brought disappointment for those expecting rapid clinical transformation. The anticipated revolution in personalized medicine did not materialize on the promised timeline. By 2010, a decade after the triumphant White House announcement, the medical community was reassessing the project's impact.

The New York Times article "A Decade Later, Genetic Map Yields Few New Cures" reported that after ten years of effort, geneticists were "almost back to square one in knowing where to look for the roots of common disease." The problem was not with basic research, which had indeed been revolutionized, but with clinical translation and the treatment of complex, common diseases.[3]

Scientific American published "Revolution Postponed: Why the Human Genome Project Has Been Disappointing," noting that while the project had "revolutionized the pace and scope of basic research," it had fallen far short of the medical miracles that scientists had promised. The expected genetic tests for common diseases and personalized preventive therapies had not appeared.[4]

Underlying this disappointment was complexity. Common diseases like heart disease, diabetes and psychiatric disorders did not follow simple genetic patterns. The genetic architecture of complex diseases proved far more intricate than early models had anticipated, involving thousands of genetic variants, gene-environment interactions and epigenetic factors.[4][6]

Some critics argued that the project had been oversold and that limited clinical value had emerged, particularly for psychiatric disorders and common diseases. Others cautioned that the timeline for translation had been unrealistic rather than the underlying concept.[31][32][4]

From the perspective of the Hype Cycle, this period represents the Trough of Disillusionment for genomics as a clinical tool. Expectations reset, frustration grew and a gap opened between the promise of the genome and the realities of medical practice.

The plateau (2015-2025)

A different picture emerges when the horizon is extended. Twenty-five years after the project's launch and fifteen years past the most visible disappointment, assessments have shifted dramatically. Recent reflections on the HGP's silver anniversary describe it as an "absolute, smashing success" with a "profoundly positive impact on human health."[8][6]

The transformation spans drug discovery and development. Antibody therapies, including IgGs, bispecifics and antibody-drug conjugates, have benefited from genomic insights. Gene and cell therapies moved from theoretical concepts to approved treatments. mRNA vaccines, which proved critical during the COVID-19 pandemic, built directly on genomic knowledge and sequencing infrastructure.[33][8]

Beyond therapeutics, genomics enabled rare disease diagnosis, pharmacogenomics for drug dosing, prenatal screening and the emerging field of precision medicine. Large-scale population genomics initiatives are reshaping prevention and early detection strategies.[34][6]

The HGP also transformed how science is conducted. It drove advances in sequencing technologies, spawned new fields such as bioinformatics, normalized international collaboration at unprecedented scale and established norms of rapid open data sharing through the Bermuda Principles.[1][7]

Researchers involved in the HGP emphasize a key insight about expectations. One leader reflected that people "had huge expectations" and were disappointed after ten years, even though "everything we had predicted was starting to happen, but not on the timeline people hoped for," concluding that the project shows how "people overestimate what they can do in the short term, and underestimate what they can achieve in the long term."[6][8]

For critics who argued that the $2.7 billion investment was unjustified, retrospective economic analyses estimate that HGP-related activity generated over $700 billion in economic output and helped catalyze an entire genomics industry. One researcher called it "the single most transformative event in the history of biological science."[35][33]

Comparing the Hype Cycles: Human Genome Project and AI

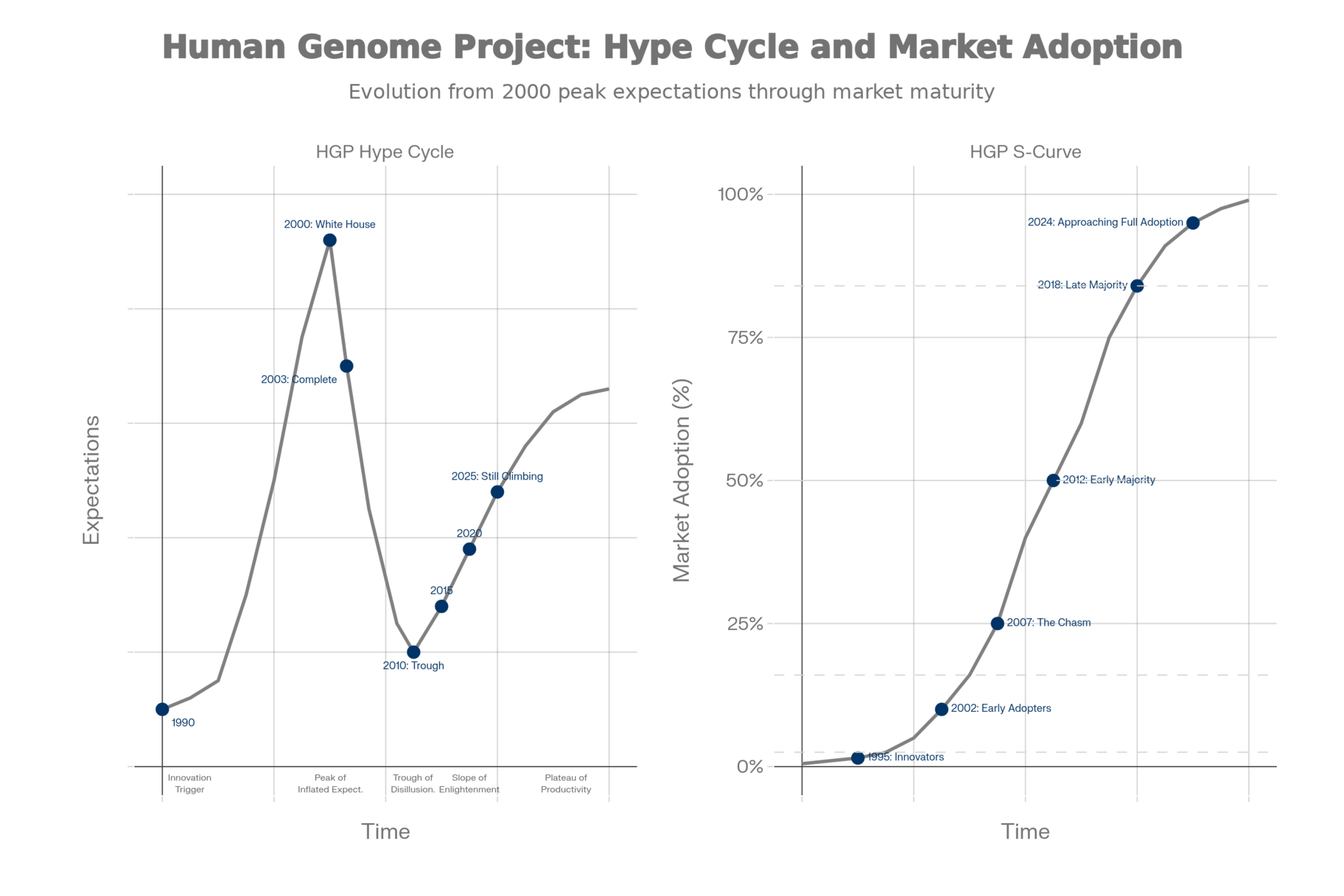

The parallels between the Human Genome Project and artificial intelligence in life sciences become particularly clear when we visualize their respective journeys through the Gartner Hype Cycle.

Side-by-side comparison for the Human Genome Project showing the Hype Cycle (left, tracking expectations over time) and S-Curve (right, tracking market adoption). Blue markers are placed directly on the gray reference curves to show HGP's position at specific years.

Side-by-side comparison for AI in Life Sciences showing the Hype Cycle (left, tracking expectations over time) and S-Curve (right, tracking market adoption). Red markers are placed directly on the gray reference curves. Solid markers show historical/present data through 2025; hollow markers show projected future positions.

Both technologies followed remarkably similar patterns:

Innovation Trigger to Peak (HGP: 1990-2000 | AI: 2020-2024). Both experienced approximately a decade of building momentum, technological advancement and growing excitement. For the HGP, this culminated in the June 26, 2000 White House announcement. [1][26] For AI in life sciences, ChatGPT's late 2022 launch and explosive growth through 2023-2024 represented the breakthrough moment that captured global attention and drove expectations to unprecedented heights. [17][18][19]

The Peak of Inflated Expectations. Both technologies reached peaks characterized by sweeping promises about revolutionizing healthcare. Clinton's proclamation that genomics would "revolutionize the diagnosis, prevention and treatment of most, if not all, human diseases" finds its parallel in today's claims that AI will fundamentally transform every aspect of life sciences from drug discovery to patient care. In both cases, media coverage intensified, investment surged and expectations reached levels that implementation could not immediately satisfy.[36][1]

Descent into the Trough (HGP: 2003-2010 | AI: 2025-present). Both experienced a sobering recalibration period. For the HGP, the 2010 headlines declaring "few new cures" and "revolution postponed" captured the disappointment. [3][4] For AI, the current statistics tell a similar story: 95% of pilots failing, 80% reporting no ROI, and 81% citing accuracy and efficiency barriers. [10][9][15] In both cases, the gap between near-term expectations and actual implementation capabilities created frustration and skepticism.

Time to plateau. The HGP took approximately 25 years from launch to widespread recognition of transformative success (1990-2025). If AI follows a similar trajectory, we might expect another 15-20 years before its full transformative potential is realized and broadly recognized across the life sciences industry.[8][6] However, given the speed of AI adoption, this timeline is likely too be shortened significantly, perhaps on the order of 5-7 years.

The key similarity is not merely that both followed a hype cycle, but that both represent fundamental paradigm shifts in how life sciences research and development are conducted. The HGP was seen as a major paradigm-shifting advancement for the life science industry, and AI is viewed similarly today in terms of anticipated transformative impact and value.[22][35][36][7]

Lessons from the Human Genome Project for AI adoption

The Human Genome Project's trajectory through these phases provides several instructive lessons for managing AI expectations and investments in life sciences today.

Lesson one: Timeline expectations matter more than technology potential

The HGP's underlying value was rarely doubted among experts. The controversy centered on timing: would the investment pay off quickly enough and in the forms people expected? Early advocates, including Clinton and Collins, made aggressive short-term predictions about clinical applications that proved too optimistic.[2][1]

The genomics experience shows that transformative technologies can take 10-15 years longer than initial promises suggest before delivering widespread value. For AI in life sciences, this suggests that if boards, investors and leadership teams evaluate AI almost exclusively on 12-24 month ROI windows, they may misjudge the role of foundational investments that pay off later.[21][15]

Lesson two: Complexity reveals itself through implementation

Genomics showed that complexity is often underestimated. The simple model of "one gene, one disease" did not hold for most common conditions, and understanding polygenic risk and gene-environment interactions required new methods, data and conceptual frameworks.[4][6]

AI in life sciences is revealing its own forms of complexity: data quality issues, integration challenges, model governance, regulatory scrutiny, workforce skills and the need for domain expertise to interpret AI outputs. The HGP experience shows that when complexity surfaces, it signals that implementation and supporting infrastructure need to adapt, not that the underlying technology lacks value.[15][16][21]

Lesson three: Infrastructure value often precedes application value

One of the HGP's most significant contributions was infrastructure: sequencing platforms, reference genomes, analytical tools, trained talent and global databases. These foundations enabled later breakthroughs that were not obvious in 2000.[33][7]

AI in life sciences has a similar infrastructure dimension: data governance frameworks, standardized ontologies, integrated data platforms, MLOps capabilities, model validation processes and cross-functional operating models. The genomics experience shows that such infrastructure investments can appear slow or indirect at first yet become the essential enablers of later high-value applications.[21][15]

Lesson four: Partnerships and ecosystems accelerate progress

The HGP benefited from international collaboration, public-private partnerships and a commitment to open data sharing that created network effects and enabled rapid downstream innovation. The Bermuda Principles established norms of releasing sequence data within 24 hours, which maximized the project's impact across the scientific community.[1][7]

For AI, MIT's research suggests that organizations partnering with specialized vendors see materially higher success rates (67%) than those trying to build everything internally (33%). The lesson from genomics is that structured partnerships that combine external platforms with internal domain expertise and governance can deliver better outcomes than purely internal builds.[10]

Lesson five: Crossing from early adopters to mainstream takes persistence

Genomics moved from research environments to clinical practice gradually. Early applications in rare monogenic diseases provided important proof points, but broader adoption in common disease management and routine care took far longer than initial public rhetoric suggested.[32][6]

AI in life sciences is beginning to see compelling use cases in areas such as literature review, coding, structured data abstraction, clinical note generation and some aspects of drug discovery. Moving from these early adopters to routine use across large organizations will require years of iterative refinement, standards development and regulatory alignment, similar to genomics' gradual mainstreaming.[14][37][13]

Applying lessons to AI in the life sciences today

The Human Genome Project and AI in life sciences share fundamental characteristics as paradigm-shifting technologies with transformative potential. Drawing from the genomics experience, several practical principles emerge for leadership teams navigating AI adoption.

Distinguish between judging the technology and judging the timing

The HGP experience shows that it is possible to be broadly right about a technology's transformative potential yet significantly wrong about timelines and near-term manifestations.[6][8]

For AI, this argues for evaluating initiatives along two axes:

Strategic relevance: Is this application directionally aligned with where the industry is heading and with your long-term strategy?

Timing and readiness: Is now the right moment for your organization to pursue this specific use case, given your data, processes, culture and regulatory environment?

This makes it easier to say "not yet" to certain AI applications without falling into "never," and to avoid both blind enthusiasm and premature dismissal.

Invest in foundational capabilities with explicit time horizons

Drawing from the genomics experience, leaders can categorize AI investments into:

Foundational investments (data quality, governance, platforms, skills) with 3-7 year horizons.

Application pilots (specific use cases) with 12-24 month horizons.

Being explicit about these horizons helps avoid judging foundational work solely by near-term ROI and helps ensure pilots are scoped realistically.[15][21]

Use partnerships strategically

Genomics benefited from a mix of public and private actors, with different strengths. In AI, MIT's research shows that organizations partnering with specialized vendors see materially higher success rates than those trying to build everything internally.[10]

For life sciences organizations, this implies that:

Purely internal builds may make sense for a small number of highly strategic, sensitive capabilities.

For many other applications, structured partnerships that combine external platforms with internal domain expertise and governance can deliver better outcomes.

The key is to treat partnerships as strategic vehicles with clear accountability, not as shortcuts that substitute for understanding the underlying problems.

Communicate expectations explicitly, inside and outside the organization

One of the challenges in the HGP era was the gap between nuanced expert expectations and simplified public narratives. AI faces a similar communications risk: nuanced internal views can coexist with exaggerated external claims, creating confusion among employees, regulators, patients and investors.[27][4]

Leadership teams can mitigate this by:

Clearly articulating what AI is expected to do in the near term (e.g., efficiency gains, better decision support) versus what remains speculative.

Framing AI as a set of tools that must be embedded into processes, not as an autonomous solution.

Regularly updating stakeholders on what has worked, what has not and what has been learned.

This helps avoid both inflated internal expectations and backlash when early projects encounter challenges.

Where AI in life sciences goes from here

The Human Genome Project provides a useful reference point for thinking about AI's potential trajectory over the next decade and beyond.

Near term (2026-2027): navigating the trough

The next two to three years may resemble the "difficult middle" that genomics experienced after its initial peak of excitement. We may see continued disillusionment as more pilot projects fail to scale, as hidden costs emerge, as organizations confront data shortcomings and as regulatory and ethical questions become more salient.[10][15]

At the same time, this period is likely to be pivotal for building the foundations that will determine which organizations eventually benefit most. Data governance frameworks, AI operating models, vendor ecosystems and internal skills will either be strengthened or neglected.[21][15]

The genomics experience suggests that organizations that continue to invest thoughtfully through this phase, without overextending or abandoning efforts, are more likely to be positioned for later gains.

Medium term (2027-2030): patterns of success become clearer

As in genomics, certain AI applications will start to show more consistent patterns of success. In drug discovery, this may include AI-augmented hit finding, optimization of lead compounds and better triaging of targets. In clinical development, AI may increasingly assist with protocol design, site selection, patient recruitment and safety signal detection.[37][38][39][13]

In commercial and medical affairs, AI-enabled analytics, targeting and engagement orchestration will mature from fragmented tools to more integrated systems.[37][21]

The parallel to the post-HGP period is that once specific applications demonstrate repeatable value under real-world constraints, diffusion among the early majority can be relatively rapid, particularly for organizations that invested early in foundations.

Long term (2030+): convergence and integration

Beyond 2030, the most important AI impacts in life sciences may come from convergence:

AI combined with multi-omics data for more precise disease subtyping.

AI coupled with real-world data for adaptive trial designs and post-market surveillance.

The genomics experience shows that transformative technologies often deliver their biggest effects through second-order applications and combinations with other tools, rather than through the most obvious early promises. The HGP's most significant contributions included applications its designers did not anticipate, such as enabling mRNA vaccines.[8][6]

Foundational readiness and calibrated expectations

The Human Genome Project and artificial intelligence in life sciences represent similar phenomena: major paradigm-shifting advancements with anticipated transformative impact on the life science industry.[35][7][22]

Both technologies followed remarkably parallel paths through the Gartner Hype Cycle. Both experienced peaks of inflated expectations fueled by sweeping promises of revolutionary change. Both encountered troughs of disillusionment when near-term implementation proved harder and slower than anticipated. Both ultimately, or in AI's case, potentially, delivered transformative value on longer timelines than initial hype suggested.[1][4][6][8]

The Human Genome Project teaches us several enduring lessons about managing transformative technologies:

For life science leaders in late 2025, the practical question is not "Is AI overhyped?" but rather "What can we learn from previous paradigm shifts about how to navigate this one strategically?"

The leaders who will succeed and realize the full potential of AI in their organizations will be those who understand the value of foundational readiness and visionary yet calibrated expectations. Foundational readiness means investing in data governance, integration capabilities, change management and strategic partnerships even when immediate ROI is unclear. Calibrated expectations mean setting realistic timelines, communicating nuanced views to stakeholders and evaluating AI investments on both near-term milestones and long-term strategic positioning.

The technology is real. The timeline may be longer than anticipated. The work is harder and more complex than early marketing suggested. And, as the Human Genome Project demonstrates, the opportunity is worth it, provided we navigate the trough with clear eyes, grounded expectations and a long enough horizon.[35][6][8]

The organizations that continue to invest thoughtfully through the difficult middle, that build foundations while others panic or abandon efforts, and that learn from the patterns revealed by earlier paradigm shifts will be those best positioned to realize AI's transformative potential in life sciences.

References

National Human Genome Research Institute. "Human Genome Project Timeline." Genome.gov, 4 July 2022, https://www.genome.gov/human-genome-project/timeline

Horgan, John. "Revolution Postponed: Why the Human Genome Project Has Been Disappointing." Scientific American, 30 Sept. 2010, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/revolution-postponed/

Wade, Nicholas. "A Decade Later, Genetic Map Yields Few New Cures." The New York Times, 12 June 2010, https://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/13/health/research/13genome.html

Horgan, John. "Revolution Postponed: Why the Human Genome Project Has Been Disappointing." Scientific American, 30 Sept. 2010, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/revolution-postponed/

"The Human Genome Project cost $2.7 billion. 20 years later, why didn't we wait for cheaper tech?" Reddit, 11 July 2020, https://www.reddit.com/r/askscience/comments/hpt7ab/the_human_genome_project_cost_27_billion_20_years/

Joly, Yann, et al. "The Fortunes of Genomic Medicine: A Quarter Century of Promise." PLOS Genetics, 16 July 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12336957/

Green, Eric D., et al. "The Human Genome Project: big science transforms biology and medicine." Genome Research, 23(9), Sept. 2013, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4066586/

"Silver Anniversary of the Human Genome Project." GEN, 13 June 2025, https://www.genengnews.com/topics/genome-editing/silver-anniversary-of-the-human-genome-project/

Bughin, Jacques, et al. "The State of AI: Global Survey 2025." McKinsey & Company, 4 Nov. 2025, https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/quantumblack/our-insights/the-state-of-ai

Challapally, Aditya, et al. "MIT report: 95% of generative AI pilots at companies are failing." Fortune, 18 Aug. 2025, https://fortune.com/2025/08/18/mit-report-95-percent-generative-ai-pilots-at-companies-failing-cfo/

"Gartner Hype Cycle for AI 2025: What the Future Holds." testRigor, 19 Oct. 2025, https://testrigor.com/blog/gartner-hype-cycle-for-ai-2025

"Generative AI and the Trough of Disillusionment." CIGI, 17 Nov. 2024, https://www.cigionline.org/articles/generative-ai-and-the-trough-of-disillusionment/

"Survey Shows How AI Is Reshaping Healthcare and Life Sciences." NVIDIA Blog, 5 Mar. 2025, https://blogs.nvidia.com/blog/ai-healthcare-life-sciences-survey-2025/

Lee, Stephanie. "2025: The State of AI in Healthcare." Menlo Ventures, 20 Nov. 2025, https://menlovc.com/perspective/2025-the-state-of-ai-in-healthcare/

"Are Life Sciences Behind in the Adoption of AI?" IQVIA, 11 Dec. 2025, https://www.iqvia.com/locations/united-states/blogs/2025/12/are-life-sciences-behind-in-the-adoption-of-ai

Khurana, Anish. "What We Learned at ACDM: A Reality Check on AI Adoption in Life Sciences." Saama, 9 July 2025, https://www.saama.com/what-we-learned-at-acdm-a-reality-check-on-ai-adoption-in-life-sciences/

"ChatGPT's second birthday: What will gen AI (and the world) look like in another 2 years?" VentureBeat, 7 Dec. 2024, https://venturebeat.com/ai/chatgpts-second-birthday-what-will-gen-ai-and-the-world-look-like-in-another-2-years

"The AI Hype Cycle: Boom, Bust, or Breakthrough?" Andrew Coyle, 11 Nov. 2025, https://www.andrewcoyle.com/blog/the-ai-hype-cycle-boom-bust-or-breakthrough

"The state of AI in 2023: Generative AI's breakout year." McKinsey & Company, 31 July 2023, https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/quantumblack/our-insights/the-state-of-ai-in-2023-generative-ais-breakout-year

"We analyzed 4 years of Gartner's AI hype so you don't make a bad investment." Pragmatic Coders, 11 Aug. 2025, https://www.pragmaticcoders.com/blog/gartner-ai-hype-cycle

"AI in Life Sciences Commercialization." IQVIA, 18 Aug. 2025, https://www.iqvia.com/library/white-papers/ai-in-life-sciences-commercialization

Smith, Lloyd M., et al. "The Human Proteoform Project: Defining the human proteome." Science Advances, 11 Nov. 2021, https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abk0734

Collins, Francis S., et al. "Twin peaks: the draft human genome sequence." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 28 Feb. 2001, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC138909/

National Human Genome Research Institute. "The Human Genome Project is simply a bad idea." Genome.gov, 5 May 2024, https://www.genome.gov/virtual-exhibits/human-genome-project-is-simply-a-bad-idea

Erickson, Jonathan. "Some history of hype regarding the human genome project and genomics." The Tree of Life, 6 Dec. 2014, https://phylogenomics.me/2014/12/07/some-history-of-hype-regarding-the-human-genome-project-and-genomics/

"White House Press Release." DOE Human Genome Project, 25 June 2000, https://doe-humangenomeproject.ornl.gov/white-house-press-release/

"Human Genome Project ten years on: Breakthrough or hype?" Progress Educational Trust, https://www.progress.org.uk/human-genome-project-ten-years-on-breakthrough-or-hype/

"Human Genome Project." Wikipedia, 15 Nov. 2001, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_Genome_Project

"The Human Genome Project (1990-2003)." The Embryo Project Encyclopedia, 5 May 2014, https://embryo.asu.edu/pages/human-genome-project-1990-2003

"The Human Genome Project Turns 20: Here's How It Altered the World." MIT Biology, 13 Apr. 2023, https://biology.mit.edu/the-human-genome-project-turns-20-heres-how-it-altered-the-world/

Finch, Samantha. "Human Genome Project: Triumph or failure?" Front Line Genomics, 1 Aug. 2021, https://frontlinegenomics.com/human-genome-project-triumph-or-failure/

"Human genome at ten: Science after the sequence." Scientific American, 22 June 2010, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/human-genome-at-ten/

"Economic Impacts of Human Genome Project." Battelle, 14 Apr. 2011, https://www.battelle.org/docs/default-source/misc/battelle-2011-misc-economic-impact-human-genome-project.pdf

"The Evolving Global Landscape of Genomic Initiatives." IQVIA, 25 Sept. 2025, https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/library/white-papers/2025/the-evolving-global-landscape-of-genomic-initiatives.pdf

"Economic Impacts of Human Genome Project." Battelle, 14 Apr. 2011, https://www.battelle.org/docs/default-source/misc/battelle-2011-misc-economic-impact-human-genome-project.pdf

"A Historical Model for AI Regulation and Collaboration." Stanford Social Innovation Review, 30 June 2024, https://ssir.org/articles/entry/human-genome-project-artificial-intelligence

"How Emerging AI Capabilities Are Reshaping Life Sciences." IQVIA, 22 Oct. 2025, https://www.iqvia.com/blogs/2025/10/how-emerging-ai-capabilities-are-reshaping-life-sciences

"AI Compute Demand in Biotech: 2025 Report & Statistics." Intuition Labs, 26 Nov. 2025, https://intuitionlabs.ai/articles/ai-compute-demand-biotech

"Scaling gen AI in the life sciences industry." McKinsey & Company, 9 Jan. 2025, https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/life-sciences/our-insights/scaling-gen-ai-in-the-life-sciences-industry

"Reimagining life science enterprises with agentic AI." McKinsey & Company, 7 Sept. 2025, https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/life-sciences/our-insights/reimagining-life-science-enterprises-with-agentic-ai